2 Computational film analysis

Definitions should be like maps: they help you explore the ground; they are not substitutes for exploration.

Brian Aldiss (1973: 3)

2.1 What is computational film analysis?

Computational film analysis employs the methods and tools of statistics, data science, information visualisation, and computer science in order to understand form and style in the cinema.

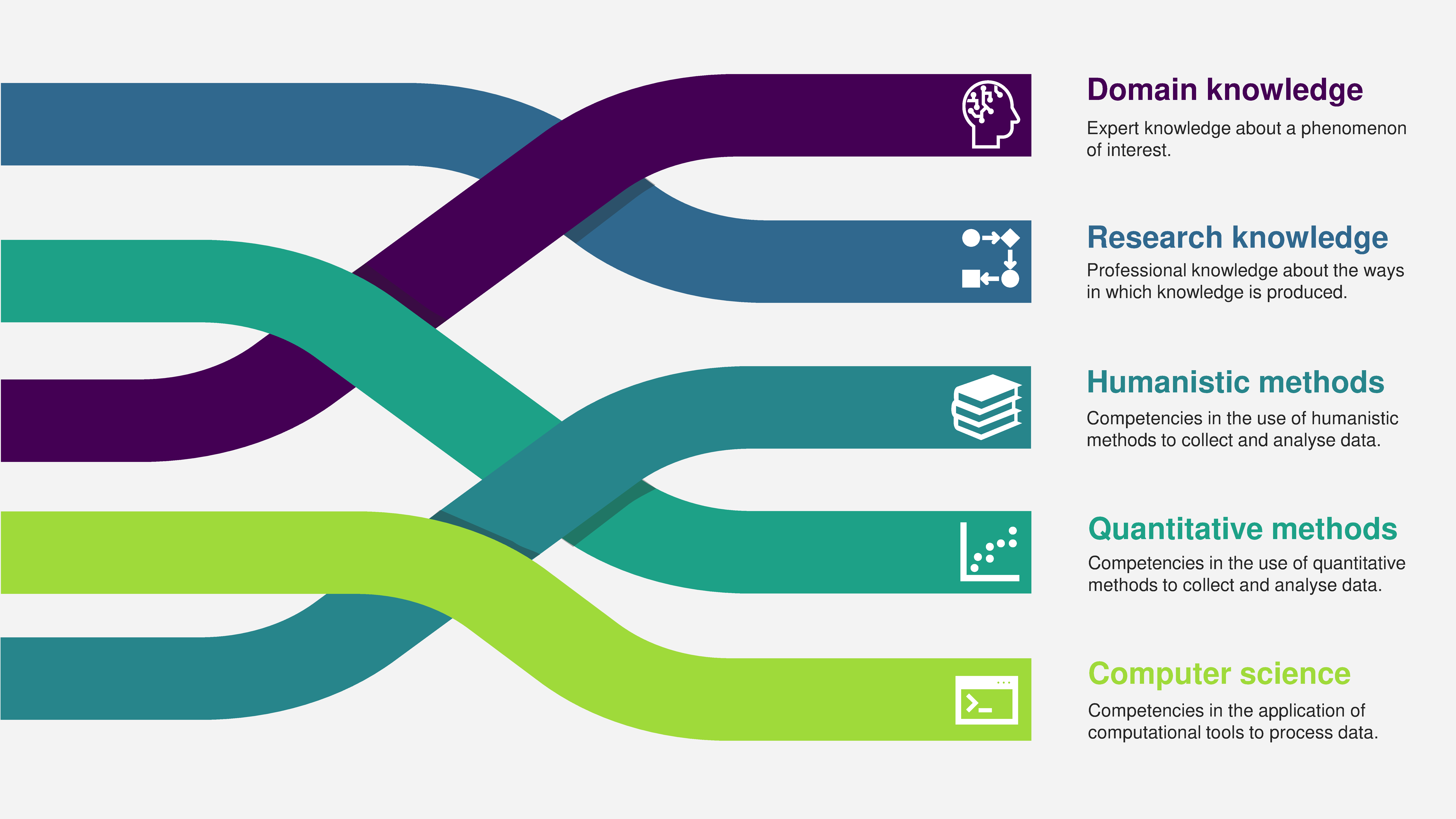

Computational film analysis is a post-disciplinary complex. That is to say, that as a field of inquiry belonging both to the digital humanities and the study of film it exists as a collection of interconnected systems weaving together the specialist domain knowledge of a phenomenon of interest in the humanities (the cinema); knowledge about the design, execution, and validation of research projects; competencies in the use of humanistic and quantitative methods to collect and analyse data; and competencies in the application of computational tools to process that data. By definition, a computational film analysis research project is engaged with every element in the complex (Figure 2.1), though each project will engage with each element in different ways.

Figure 2.1: The complex of computational film analysis. ☝️

There is an ordering to the elements in the complex. Every CFA project begins by (1) framing questions about the cinema, which are then (2) operationalized as an achievable research project by defining the sample to be studied, the concepts in which the researcher is interested and the variables that represent them, and how those variables will be measured. This requires (3) the selection of an appropriate set of humanistic and quantitative methods for data collection, analysis, and reporting; and (4) the selection of a set of computational tools to implement those methods. Applying computational tools to data will (5) result in a set of outputs (statistical summaries, data visualizations, models, etc.) that (6) must be interpreted in the context of the methods selected. Interpreting these results will (7) supply answers to the research questions making it possible to (8) judge the meaning of those results and satisfy the researcher’s curiosity about the cinema.

The ordering of a CFA project begins and ends with domain knowledge. The questions and answers of CFA belong to the study of film. It is only in this context that those questions and answers have any meaning. But those questions can only be answered by engaging with the other elements of the complex in order. As it moves through stages one to four in Figure 2.2, the representation of a film becomes more abstract as it is turned into data capable of being analysed by a computer. Returning through steps five to eight of Figure 2.2, the representation of a film becomes more concrete leading us to make empirical statements about the cinema. Every CFA project necessarily begins and ends with the cinema.

Figure 2.2: The process of computational film analysis. ☝️

My 2015 conference paper ‘The time contour plot: graphical analysis of a film soundtrack’ (Redfern, 2015b) illustrates this process in practice. I was (1) interested in understanding how the sound design in the short horror film Behold the Noose (Jamie Brooks, 2014) created a frightening experience for the viewer. I chose to focus on (2) the temporal organisation of the soundtrack and its relationship to the structure of the film, changes in sound energy at different scales (event, scene, and segment), and the dynamic relationship between sound and silence. The methods I selected were (3) the spectrogram of the short-time Fourier transform of the soundtrack and the normalised aggregated power envelope, and these were (4) implemented using the tuneR and seewave packages for the statistical programming language R. The results of applying these methods were (5) visual representations of the structure of the soundtrack that (6) I interpreted given my understanding of the quantitative methods employed in order to (7) describe and analyse the key features of the soundtrack I had selected as relevant. I could then (8) explain how the filmmakers had organised this aspect of film style in order to impact the audience. This method is covered in Chapter 4 of this book.

Computational film analysis is more than the statistical analysis of film style. Although CFA employs statistical methods, it inherits a broader outlook on what is possible with quantitative methods and computational tools from data science to embrace exploratory data analysis, statistical modelling, machine learning, data visualisation, and computer programming in order to tell the story of the data. CFA falls within the scope of a greater data science described by (Donoho, 2017) which comprises the tasks of data gathering, preparation, and exploration; data representation and transformation; computing with data; data modelling; data visualisation and presentation; and science about data science.

2.2 Where does computational film analysis fit? Part I

Burdick et al. (2012: 122) define the digital humanities broadly as ‘new modes of scholarship and institutional units for collaborative, transdisciplinary, and computationally-engaged research, teaching, and publication’ and as ‘less a unified field than an array of convergent practices that explore a universe in which print is no longer the primary medium in which knowledge is produced and disseminated.’ More concretely, the term ‘digital humanities’ describes two related areas of research: the analysis of culture (broadly and variously defined) using digital toolkits that enable researchers to search and retrieve texts from databases, automate analyses, and detect patterns and structures within and between texts; and the study of the impact of digital technologies on humanities research (Masson, 2017). From the perspective of the digital humanists, the objectives of the digital humanities in analysing culture are the same of those as the non-digital humanities, though the methods are not. Despite this common goal between digital and non-digital humanists, there is a history of resistance to the digital humanities that regards it as an illegitimate way of understanding culture because it uses ‘digital toolkits.’

The estrangement between the digital and non-digital humanities occurs because each uses ‘humanities’ to refer to a different thing. For the digital humanist, the humanities are an object of study and digital refers to the nature of the methods applied to that object for analysis. For example, Silke Schwandt defines the digital humanities as ‘a growing field within the Humanities dealing with the application of digital methods to humanities research on the one hand as well as addressing questions about the influence of digital practices on research practices within the different humanities disciplines on the other’ (Schwandt, 2020: 7, my emphasis). Non-digital humanists do not accept this position because they conceive the humanities not as an object of inquiry but as a way of knowing about the world distinguishable from the natural sciences (Osborne, 2015: 16). Just as the term scientific method defines an empirical method of knowledge production characterised by a canonical form of inquiry that is relatively stable across scientific disciplines, the term humanities method defines a historicist-perspectivist mode of knowledge generation held to be equally valid across humanities disciplines (Knöchelmann, 2019). This ‘high humanist’ stance insists the humanities are ‘a sui generis and autonomous field of inquiry, approachable only by means of a special sensitivity produced by humanistic training itself’ (Slingerland, 2008: 2). Because the methodologies used by digital humanists come from the sciences – computer science, data science, statistics, etc. – the knowledge they produce is the product of the scientific method and is, therefore, scientific knowledge. By definition, the knowledge produced by the digital humanities cannot be a part of humanist knowledge about culture because it is produced by the wrong way of knowing.

The difference between the digital and non-digital humanities can be expressed as a difference of disciplinarity. Jan Parker argues that disciplines are a ‘communities of practice’ characterised by ‘non-generic epistemological models:’

For many disciplines, surely, the defining, quintessential element is a core process: an underpinning unifying activity that gives the discipline its distinctive tone and value. For Humanities disciplines the core is the critical, mutual engagement with humanities texts (Parker, 2002: 379).

Given this definition of disciplinarity, it is clear to see why non-digital Humanists reject the application of digital methods as a legitimate way of knowing for failing to participate in the ‘underpinning unifying activity’ even though those methods may enable researchers to engage – mutually and critically – with humanities texts. The digital humanities contribute to the understanding of the human society and culture, but they do not participate in the humanities as a way of knowing, a set of practices by which knowledge is produced, conformed, implemented, preserved, and reproduced, that is institutionalised and regulated by universities, scholarly societies, and publications (Post, 2009).

Robert Post argues that, unlike the sciences, the humanities are resistant to methodological and institutional reformulations that challenge disciplinary boundaries, with new and emerging fields assimilated into existing methodologies:

It is a genuine puzzle why the humanities cannot seem easily to transcend traditional disciplinary methods like the textual exegesis of literary criticism, the analytics of philosophy, the narratives of history, or the cultural hermeneutics of anthropology. … it has in fact proved surprisingly difficult to generate stable and enduring new disciplinary formations in the humanities. The proliferation of new disciplines in the sciences depends in part on the fact that new domains of knowledge often require new techniques of knowledge acquisition, so methodology necessarily changes in step with the subject matter to be studied. In the humanities, by contrast, new domains of knowledge are quite regularly assimilated to traditional disciplinary methods (Post, 2009: 757-758).

The digital humanities have emerged as an enduring area of research and teaching, if not quite a stable one, but have not been assimilated into existing humanities disciplines smoothly. Indeed, the assimilation of digital methods into the humanities has been actively resisted (Allington et al., 2016; Da, 2019; Fish, 2019; Greetham, 2012; Konnikova, 2012).

The critique of disciplinarity in all areas of the sciences and the humanities has focussed on the limits of specialisation, which blinds researchers to the broader context in which phenomena exist; and that in focusing on too narrow a topic fails to deal with the complexity of the real world, imposing a past approach onto the present that limits the possibilities for create breakthroughs, and which discounts or ignores alternative ways of knowing (Osborne, 2015; Repko et al., 2019; Wilson, 2009). Andrew Sayer (2000) argues this arises because disciplines are both parochial, unable to pose questions beyond their limits that are strongly policed, and imperialist, claiming intellectual territories as their own irrespective of the work of others.

The perennially recommended solution is to go beyond boundaries, defeating the parochial and imperialist imperatives of disciplinarity, to engage in research that is either multidisciplinary, by bringing together researchers from a range of disciplines to collaborate with each drawing on their own disciplinary expertise, interdisciplinary, by integrating knowledge and methods from different disciplines, or transdisciplinary, to create a unity of intellectual frameworks that are not bound by disciplinary perspectives (Stember, 1991). These approaches are a response to reductionist disciplinary specialisation grounded in the dichotomous ‘either-or’ thinking of the dominant Western intellectual tradition that maintains a distinction between the sciences and the humanities (Newell, 2010: 360; M. Smith, 2017: 1-5). However, multidisciplinary research remains firmly grounded in the disciplinary specialisation of the participants, and interdisciplinary research remain tied to disciplinary thinking. As Louis Menand, points out

when you ask why interdisciplinarity is important, often the answer is that interdisciplinarity solves the problem of disciplinarity. But this seems a non sequitur. Interdisciplinarity is simply disciplinarity raised to a higher power. It is not an escape from disciplinarity; it is the scholarly and pedagogical ratification of disciplinarity. If it’s disciplinarity that academics want to get rid of, then they cannot call the new order interdisciplinarity (Menand, 2010: 96-97).

Attempting to leave behind disciplinarity, the transdisciplinary is an emergent phenomenon, arising through the context-specific interactions of different forms of practice to generate new ways of knowing capable of understanding the hybrid, multidimensional nature of reality and which transcend academic disciplinary structures (McGregor, 2015; Thompson Klein, 2004). However, it is difficult to identify the point at the transdisciplinary emerges so that distinguishing between inter- and transdisciplinarity is challenging and may only be possible in hindsight; while what emerges from/as the transdisciplinary may itself become institutionalised over time as a new discipline, generating new academic structures with clearly defined boundaries. A potential danger for the digital humanities is it that becomes institutionalised as just another discipline, with its own professional societies, journals, conferences, degree programmes, and university departments – all of which already exist – that define (imperially) and police (parochially) its limits. For these reasons, I prefer not to use the term transdisciplinary in reference to the digital humanities, though as we have seen above, other digital humanities researchers describe their work in these terms.

Randi Gray Kristensen and Ryan Claycomb describe post-disciplinarity, an alternative formulation of the transdisciplinary, as the goal of the critique of disciplinarity:

While the anti-disciplinary actively challenges the taxonomic effort to organise, categorise, and delimit knowledge into discrete, sanctioned modes of inquiry, the post-disciplinary (or its rough cognate, the transdisciplinary) functions as if those discrete models no longer matter. To construct a perhaps simplistic narrative of such a progression, we might suggest that disciplinarity has come under critique from an anti-disciplinary stance, which initially gave rise to current rhetoric in savour of multi- and interdisciplinary approaches, approaches that respectively combine and cross methodologies, but that still adhere to the significance of disciplines in the first place … The post-disciplinary, then, is the perhaps utopian goal of the anti-disciplinary critique, a state of knowledge production that draws on the potential of multi- and interdisciplinary inquiry without the professional surveillance and institutional policing that remains implicit in most forms of these modes (Kristensen & Claycomb, 2010: 5).

As a utopian ideal, post-disciplinarity has been described as a form of resistance to being co-opted into existing disciplinary formulations to ‘achieve and maintain [a] radical intellectual freedom’ (Kristensen & Claycomb, 2010: 6) and ‘a liberated mode of imagination and curiosity that advances academic freedom and flexibility to see, do, and be anew’ (Pernecky, 2020: 6, original emphasis). Post-disciplinarity has an open, democratic, and creative relationship with knowledge made possible by breaking with the social structures and cultural practices that define disciplines:

[Post-disciplinarity] extends to questioning conventional norms and processes of knowledge production, dissemination, and communication; it is an invitation to debate about the genres that have received a privileged position in scholarly activities; and it challenges the established view about the scope and limits of what is possible, relevant, desirable, and even credible in academic terms (Pernecky et al., 2016: 36).

Post-disciplinarity does not mean abandoning methodological rigour for purposeless eclecticism. Rather it is grounded in the recognition that there are different ways of knowing about complex and diverse phenomena, that no one method will be able to answer all the questions we wish to ask, and that to answer those questions researchers should have the freedom to select and combine different methodologies creatively and disobediently without a fear of discipline. The goal of research is to produce original knowledge about the world; not to perpetuate disciplines.

Discarding disciplinarity requires us to find a new term to describe the digital humanities as a diverse field of inquiry. The term I prefer is complex, the etymology of which lies in the Latin complecti, which means ‘to embrace’ or ‘to entwine,’ having its own roots in com, meaning ‘with, together’ and plectere, meaning ‘to braid.’ Alvila (2014: 197 ff.) argues that ‘complex’ therefore has two key characteristics, one derived from ‘braid’ or ‘fold’ that involves a type of interaction between parts, and the other arising from ‘embrace,’ ‘encircle,’ or ‘encompass,’ which conveys a sense of global shape or identity, to convey ‘the quality of those objects whose identity or meaning emerges from the interaction between two or more parts that make up a unit or entity without losing their individuality.’

The digital humanities, then, are a post-disciplinary complex, defined not by a sanctified way of knowing about culture but by the possibilities of knowing through different ways. They are characterised by question-driven rather than methods-driven research, and do not care about the provenance of the methods used to answer those questions – the only requirement is that they enable us to answer whatever questions we wish to ask about culture. In the digital humanities, there are no illegitimate ways of knowing, and methods drawn from the sciences are freely and purposefully combined with those from the non-digital humanities. Because each researcher will want to know different things about human society and culture, those methodological combinations will be unique to the questions posed so that the complex of the digital humanities is remade anew each time, entwining and embracing new strands of research. There can be no discipline-defining core process in these circumstances and there is as much variation among digital humanities research projects as there is between digital and non-digital humanities research. Nevertheless, the digital humanities have a living identity as a complex embracing different ways of knowing that is enduring but ever-changing, and which arises from myriad methodological combinations that distinguish it from the disciplinary humanities. The constant remaking of the digital humanities in the absence of an ‘underpinning unifying activity’ armours the digital humanities against the fate of disciplinarity – though that danger will be ever present.

As a manifestation of the digital humanities applying computational, data-driven methods to questions about the form and style of motion pictures, computational film analysis inherits these qualities as a post-disciplinary complex. Each piece of research employing computational approaches to film style will create a unique arrangement of methods in response to the different questions asked by researchers, combining humanistic modes of inquiry (historical research, philosophical approaches, narrative inquiry, textual analysis, etc.) with methods drawn from a wide range of research fields, including psychology (Cutting, 2021), bioacoustics (Redfern, 2020c), biology (May & Shamir, 2019), climate science (Redfern, 2014c), linguistics (Grzybek & Koch, 2012), quantitative economics (Redfern, 2020a), computer science and machine learning (Álvarez et al., 2019), and many others, without worrying about the source of those methods. The diversity of these approaches inoculates CFA against disciplinarity, though they all have in common a shared goal: a desire to contribute to our understanding of the art of motion pictures.

2.3 Where does computational film analysis fit? Part II

How does computational film analysis fit into Film Studies? The answer is simple: it does not. There is no place for CFA within the discipline of Film Studies. This should be mourned as a loss but recognised as an opportunity to re-imagine the study of film as a post-disciplinary complex unlimited in its methodological scope.

Contemporary debates about the future of Film Studies as an academic discipline have largely focussed on the changing meaning of ‘film’ with the emergence of new, digital technologies of motion picture production and distribution that challenge the medium specificity of the cinema (Carroll, 2003: 1-9; Flaxman, 2012; Rodowick, 2008). Rick Altman, for example, refers to a ‘post-Film Studies world’ arising from the ontological uncertainty surrounding the nature of the ‘film’ object (R. Altman, 2009). At no point, however, does Altman (or indeed any other film scholar) propose changing the disciplinary nature of Film Studies. Claims for interdisciplinarity are made because different screen media are to be studied alongside one another – for example, film and television – even though the methods used for studying different screen media are the self-same historicist-perspectivist ways of knowing characteristic of the discipline of Film Studies. The ‘post-Film Studies world’ that Altman envisions represents an attempt to negotiate the meaning of ‘film’ in Film Studies while leaving the ‘studies’ in Film Studies untouched. ‘Film’ may take on new meanings or be combined with other nouns (television/media/games/etc.), but the discipline persists. The goal of redefining ‘film’ is to ensure the continuity of Film Studies.

Similarly, calls to reform Film Studies, that in the eyes of some scholars has become corrupted or lost its way, are intended to reinvigorate rather than to challenge its disciplinarity. For example, in her essay ‘Why study cinema?’, Valentina Vitali argued that Film Studies paid a high price for its institutionalisation as a discipline becoming, in her view, instrumentalised as a part of the very culture industries it seeks to critique. Film Studies should be dissolved to be replaced by

a discipline fully conscious of its role as a critical (as opposed to a formatting) operation, a body of theories and knowledge awake to the question of the productivity of studying cinema both as a medium and a particular discursive cultural form (Vitali, 2005: 288, my emphasis).

Vitali’s objective is a reformulation of the discipline, but at no point does she challenge the disciplinarity of Film Studies. Similarly, David Bordwell and Noël Carroll sought to encourage the application of new approaches to understanding the cinema by sweeping away the ‘decades of sedimented dogma’ of Grand Theory that dominated the discipline from the early-1970s to the mid-1990s and replacing it with ‘theories and theorising; problem-driven research and middle-level scholarship; responsible, imaginative, and lively inquiry’ but which nonetheless left Film Studies largely intact, re-constructing the discipline (Bordwell & Carroll, 1996: xvii).

Personally, I am comfortable with the word ‘film’ and use it without difficulty to refer to arts works and a mode of aesthetic experience that is well understood by those I converse with (I have yet to meet anyone who did not understand the phrase ‘watch a film’), even though it no longer depends on a film medium and has, to this extent, become skeuomorphic. It is the disciplinary part of Film Studies that I see as an obstacle to the future – the ‘studies’ and not the ‘film’ – because it inhibits the ways in which I and others can know about the cinema. Re-constructing or re-formulating Film Studies while retaining its core disciplinarity will not change that fact. The shift from Film Studies to the study of film is a shift from the disciplinary to the post-disciplinary, from methods-driven research to question-driven research, and from disciplinarity to complexity. Film Studies is a discipline; film as a domain of study, like the digital humanities, is a post-disciplinary complex.

Film Studies is an approach to studying film that emerged in Europe and North America in the late-1960s. In a 1968 edition of Cinema Journal, the journal of the newly named Society of Cinema Studies, the editors declared ‘we are searching for our best approach, our discipline’ (quoted in Ellis & MaCann (1982: viii, my emphasis)). There is a close relationship between method and discipline: knowledge that is a part of the discipline of Film Studies is knowledge produced by the characteristic approach of that discipline, which was determined to be critical analysis grounded in the historicist-perspectivist modes drawn from other humanities disciplines. Film Studies was conceived, parochially and imperially, as a way of knowing about the cinema grounded in humanities-based methods of inquiry (‘our best approach’), with a self-nominated group of scholars asserting ownership (‘our discipline’) of a programme of research about the cinema. Grieveson & Wasson (2008: xiii) point to the fact that the Society of Cinema Studies was born from the Society of Cinematologists, and that the dropping of the old name represented a conscious rejection of scientific approaches to the cinema and a wholehearted embrace of humanities-based methods.

There is irony here. Film Studies emerged at the same time as other ‘studies’ programmes in higher education, such as Women’s Studies, Gender Studies, Environmental Studies, etc., which were conceived as part of an anti-bureaucratic and interdisciplinary movement against the principle of disciplinarity that was grounded in a broad-based scepticism about the universality of any particular method (Menand, 2001). Film Studies, however, was conceived as singular field focussed on a limited range methods to establish it as a clearly differentiated discipline within the humanities (even though its methods were drawn from English literature, art history, and philosophy) that enabled the new discipline to become institutionalised in university departments. To the benefit of many researchers and students – including myself – it has been highly successful in achieving this goal. However, this came at a cost. David Bordwell argues that Film Studies ‘got off on the wrong foot methodologically. Instead of framing questions, to which competing theories might have responded in a common concern for enlightenment, film academics embraced a doctrine-driven conception of research’ (Bordwell, 2005b: xi, original emphasis). The institutionalisation of Film Studies admitted only a single class of methods as legitimate, cutting itself off from research by economists, sociologists, and psychologists that did not use those methods, but which might usefully contribute to our understanding of the cinema in all its complexity by answering the very same questions Films Studies attempts to answer. There is no theoretical or methodological justification for this.

The ‘paradigmatic chauvinism’ (Sternberg, 2007) of the doctrine-driven approach exhibited by Film Studies creates several problems. First, restricting the study of film to a single way of knowing about the cinema not only limits the answers we may find; it constrains the range of possible questions we can ask. The ‘best approach’ is the one that helps those researchers to answer the questions they wish to ask about the cinema irrespective of its origins. Second, alternative methodologies – and the researchers who employ them – are marginalised despite the fact they may be better suited to answering questions about the cinema. Consequently, questions are viewed as important because they conform to pre-selected methods rather than selecting methods based on the importance of the question. To this we can add that, because it developed in North America and Europe, Film Studies is grounded the Western intellectual tradition of the humanities and being limited to a single class of methods marginalises alternative approaches – and the researchers who employ them – grounded in non-Western methodologies and pedagogies (Akande, 2020). Third, film researchers and film students receive a narrow training in knowledge production, perpetuating a methodological monopoly that does not adequately prepare them to deal with real world problems because, fourth, researchers are unable to change direction in response to the exhaustion of methodological fads, the emergence of new phenomena, or the demands of other non-academic, stakeholders. For example, these problems have been acknowledged by Ian Christie, who observed at a BFI symposium on research and policymaking in the British film industry in 2011 that

meaningful research in the audio-visual field increasingly needs a multiplicity of skills and disciplines […] the problem is that the style of funding we have at the moment […] is to a single principal investigator who is in one discipline in one institution (British Film Institute, 2011: 9).

Christie went on to express the opinion that Film Studies has failed to address important issues and to impose itself on the research agenda, in part because it had generated too much qualitative research that could provide only a limited range of answers to a limited range of questions.

Computational film analysis does not fit into Film Studies because it does not participate in the ‘underpinning unifying activity’ of that discipline, namely the critical analysis of film texts by means of humanities-based methods. Nonetheless, CFA has the same goals as Film Studies scholars using humanities methods: to understand the form and style of motion pictures and to account for their functions. For CFA to contribute to our understanding of cinema it is necessary to forego the disciplinarity of Film Studies and embrace the study of film as a post-disciplinary complex in its own right. By thinking of the film as an object of inquiry rather than a discipline we free ourselves from the mundane activity of reproducing something called ‘Film Studies’ so that we ask all the questions we want to ask about the cinema and answer them.

The study of film comprises four distinct but related areas: industrial analysis, textual analysis, ethnographic analysis, and cognitive-psychological analysis (see Table 2.1). Films are analysed as institutionally produced commercial commodities that function as cultural artefacts inscribed with meanings which are consumed and interpreted by audiences whose experiences of the cinema are predicated on cognitive-psychological processes of perception and comprehension. The complexity of film as an object of inquiry requires a methodological diversity to match. No single method or class of methods is capable of answering all the questions we can ask about the cinema. The answer to a question posed in one area will often require methods derived from one or more of the others. For example, in order to answer a question about film style, such as ‘why did continuity editing emerge as the dominant style of Hollywood cinema?’ (textual analysis), we will find the answer in understanding how the film industry adopted a style and mode of producing films that was both narrationally and economically efficient (industrial analysis; see Staiger (1985: 178-180)) and in understanding how this system of editing exploits the viewer’s ability to construct a coherent spatial understanding of a scene (cognitive-psychological analysis; see Anderson (1996: 99-103)). This is not to insist on the irreducibility as a film as a phenomenon. Individual questions may be answered through the application of a specific method within a single area; but to understand the cinema in its diverseness, it is necessary to have a range of methods from which to choose.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Industrial | the political economy and organisation of film industries; technologies of film production, distribution, and exhibition; practices of film production, distribution, and exhibition; government policies; etc. |

| Textual | representation and the symbolic meanings of film; film form; film style; narrative/non-narrative structure; etc. |

| Ethnographic | the composition of audiences; rituals of cinema-going and film experiences; cultural meanings and issues of identity; etc. |

| Cognitive-psychological | the viewer’s perception of a film; communication and information in the cinema; psychological processes of meaning-making in the cinema; the psychological basis of the viewer’s response to a film; etc. |

If we approach film as a complex object of inquiry with the methodological openness this demands, researching the cinema naturally includes quantitative and computational methods, as it naturally includes historical and text-based methods, because film scholars will be faced with economic, textual, sociological, and scientific data much of which is computationally tractable. With the application of quantitative and computational methods, on their own or in combination with humanistic modes of inquiry, it becomes possible answer a far broader range of questions about the economics of the film industry, about patterns in the style and form of motion pictures, about audiences’ behaviours and attitudes, and about how we experience and make sense of the cinema (Redfern, 2013a). The methods used will come from economics, marketing, sociology, psychology, and neuroscience; but their provenance is of less interest than the fact they can contribute to an understanding of the cinema. Again, the goal is to produce knowledge about the cinema rather than to perpetuate the discipline of Film Studies. After all, students study film; not Film Studies.

As our ideas about who or what is a filmmaker change, so will our ideas about the future design of film education programmes because analysis will become a part of filmmaking. At present, filmmaking courses focus on the core skills of direction, cinematography, editing, sound design, and producing; but as data-driven AIs come to reshape and, in some cases, replace the filmmakers performing those activities, a new type of filmmaking education will be required based not only in the craft traditions of filmmaking but also in the computer and data sciences.

One approach is the Data-Driven Creativity Project (DDCP) at Curtin University, Australia, which teaches students how filmmakers’ stylistic decisions impact audiences’ attention, arousal, and emotions using data derived from eye-tracking, skin conductance level, and facial recognition studies (Bender & Sung, 2020). Adopting a CFA approach can extend a project such as this to allow students to create and analyse their own data as researchers and filmmakers, so that they can grow beyond being filmmakers and viewers who act as ‘practical psychologists’ (Bordwell, 2012) to become cinematically and scientifically experimental researchers and data-driven filmmakers.

Another way forward is to develop degree programmes designed to meet these goals combining computational film analysis, with students learning about film form and film style and developing the data science knowledge to build models of motion picture aesthetics, and computer science, in which students learn the data structures and algorithms that will allow them to engineer the software to implement the models they have developed using CFA in the production of motion pictures.

Finally, if film scholars are going to continue the work of analysing film style and film form, they will need to be able to think computationally to understand how algorithms create works of art. There is no critique of data-driven filmmaking without an understanding of data science. There are no critical operations capable of analysing the limitations and biases of those algorithms and the data used to train them (Kearns & Roth, 2020) without an understanding of how data is used in the film industry. Data-driven filmmaking requires data-driven studies of film.

2.4 Analysing films computationally

2.4.1 Analysis

In his discussion of the aesthetics of music, Roger Scruton (1997: 396-398) describes the analytical process as building a bridge from the formal structure of an artwork to the aesthetic experience it affords through the construction of a ‘critical narrative’ that enables us to experience what is there in a work of art, to experience things differently and, thereby, to help us enjoy a work of art. Analysis is differentiated from other forms of writing about film because, unlike criticism, it does not engage in value judgements; and, unlike hermeneutics, it is does not produce subjective interpretations that depend on extrinsic factors. Rather, it is focussed on the work itself and while it uses description to account for the formal structure (what), its aim is to explain the functions (why) and operations (how) of a text. Computational film analysts comprehend the structure of a text through computational means, but the goal remains the production of a critical narrative that explains the film or group of films under analysis.

Computational film analysis complements and extends existing methods used for the analysis of film style and form to bring an alternative perspective to bear on the cinema, encouraging scholars to think in new ways about old problems and to conceive novel questions to be answered (Ramsay, 2012a). CFA adopts a bottom-up data-driven approach as an alternative to the top-down doctrine-driven approach of Film Studies that allows scholars to discover unexpected relationships and potentially explicable patterns of form and style rather than being constrained by their a priori interpretations of a film (Redfern, 2015a). The digital toolkits of CFA make it possible to move smoothly between different scales of analysis from individual pixels to scenes and sequences to whole films and beyond to groups of films, allowing researchers to look at each frame in extraordinary detail and to view a corpus from a distance (T. Arnold & Tilton, 2019).

Carroll (1998) describes two modes of stylistic and formal analysis of motion pictures: a classificatory mode, which uses descriptive stylistics relationally to differentiate between groups of films based on the presence or absence of a set of formal devices; and an explanatory mode, which accounts for the significant use of stylistic and formal devices in a single film by deconstructing the functions of those devices in realizing the purposes of the film.

Computational methods can be applied in both analytical modes. The classificatory mode aligns with the application of data mining, the detection of patterns, relationships, and anomalies within large data sets, and machine learning, the automated construction of models from data with minimal human intervention, to questions of film style at the level of the corpus, analysing films based on their colour (Flueckiger, 2017), plot structure (Del Vecchio et al., 2020), editing (Cutting et al., 2010), social networks (Weng et al., 2009), shot scales (Svanera et al., 2019), or visual content (May & Shamir, 2019).

The explanatory mode aligns with the textual analysis of single films that address functional questions to explain why a film possesses the formal and stylistic qualities it does, and is capable of shifting between the micro level of individual moments in a film, to the meso level of scenes and sequences, and the macro level of the whole film itself to describe and explain the use of colour in a film (Stutz, 2021), the sound design in a trailer (Redfern, 2021c), or the relationship between multiple elements of a film’s style and its narration (Redfern, 2013b).

By adopting methods used in the data-driven creation of motion pictures, CFA can bring new methods to the analysis of motion pictures. The Prose Storyboarding Language developed by Ronfard et al. (2015) builds on research into developing artificial intelligence approaches to film production to provide a formal language for describing motion pictures shot-by-shot using a simple syntax and limited vocabulary based on film production working practices and is intended to be readable both by AI machines and humans. Although the primary purpose for the Prose Storyboarding Language is to serve as a high-level user interface for artificially intelligent filmmaking technologies, it also has applications for the close analysis of motion pictures by film scholars and can be used to describe scenes from films, communicating stylistic and formal features concisely and effectively no matter how complex the shot or sequence under analysis.

Through the application of data visualization techniques, CFA frees us from the idea that analysis in film studies is a literary activity – ‘a form of writing which addresses films as potential achievements and wishes to convey their distinctiveness and quality (or lack of it)’ (Clayton & Klevan, 2011: 1). The use of graphical methods of analysis makes it possible to place the various elements of film style in relationship to one another simultaneously to grasp the coherence of a film’s system of style rather than dealing with them singly, one by one. Andrew Klevan writes that ‘film – visual, aural, and moving – is a particularly slippery art form’ that ‘sets up peculiar problems for analysis and description because it is tantalizingly present and yet always escaping’ (2011: 71, original emphasis). Consequently, Film Studies tends to treat style as a static phenomenon, either abstracting individual scenes from the flow of the larger work or ignoring the temporal dimension altogether. Applying data visualisation to the form in the cinema enables researchers to analyse film style as dynamic rather than static, tracking the evolution of style across a single film or describing trends in the uses of formal devices across decades. CFA thus enables film scholars to approach each film as a dynamic, complex work of art in its entirety and cinema as a mass art, rather than focussing on individual devices in isolation or being restricted to small groups of films.

2.4.2 Film

Alan Marsden (2016) writes that computational approaches to aesthetic analysis impose limits on how we can think about a text, whether that be a novel, a film, a piece of music, or any other artwork because there must be a definite input to the analysis. The term film can be used materially (albeit skeuomorphically) to refer to a recording of events stored on celluloid, video tape, DVD/Blu-Ray, DCP, hard drive, etc.; or it can be used experientially, to refer to the presentation of those events on a screen as witnessed by a viewer (Redfern, 2007). In computational film analysis, film as an input can only ever be its material form. The analyst must therefore accept a certain ‘ontological rigidity’ of a film because the text must take the form of binary code with every bit determined prior to analysis. Marsden (2016: 20) argues that provided the data is recognised as standing for the text at this stage, there is no reason to locate the analysis anywhere other than the film itself and the analysis does not depend on inputs that are extrinsic to the film.

However, this does not mean that the results of an analysis are inevitable because, Marsden argues, there is no single definitive representation of an artwork that can be generated from an input; and an artwork will never be fully captured by computational methods because, in accordance with the principle of incomplete knowledge (Heylighen, 1993), any model of a film generated by the analytical process must be simpler than the object it explains. The analytical outputs of computational approaches are more fluid than the inputs because the researcher must make decisions about which aspects of a film are selected to answer their research question and which projections adequately represent those aspects. Consequently, there is not necessarily any reason ‘to believe that the particular structure in the output of the analytical process has a privileged status among the myriad other possible ways in which the input data could be structured’ (Marsden, 2016: 20).

For example, in my analysis of the sound design in the short horror film Behold the Noose (Redfern, 2015b) I extracted the soundtrack of the film. A selection has therefore been made about which aspect of the film is to be analysed (the complete soundtrack of the film); and because the input to the analytical software is necessarily binary code (a .wav file), there is an ontological equivalence between the soundtrack and the data comprising the wav file to be processed. At this stage, text equals data: a data file containing the amplitude values comprising the waveform of the film’s soundtrack could be converted to an audio file, thereby reproducing the soundtrack in its original form. The soundtrack was then processed to produce a set of projections (the spectrogram and the normalised aggregated power envelope) that represented the soundtrack with the analytical power to allow me to identify the key features to be explained. In producing these projections, some information is lost as the cost of revealing the latent structure of the data: both the spectrogram and the power envelope contain less information than the soundtrack so that neither exactly describes the film’s soundtrack, though both are illuminating about various features of that soundtrack. As Alfred Korzybski stated:

A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness (Korzybski, 1994: 58, original emphasis).

The spectrogram and the power envelope are both data structures; but at this stage, data and text are no longer ontologically equivalent – one cannot be substituted for the other. The data-based projections represent the film’s soundtrack. Using these projections, I presented a critical narrative that explained the structure and functions of the different parts of the soundtrack, the use of non-linear sound mixing, and the role of affective events and their place within the narrative-emotional economy of the film. I could have chosen an alternative set of projections (such as wavelet analysis or spectral flux) to represent the soundtrack, perhaps leading to a different critical narrative. Computational film analysis thus involves a process of transformation from film to data to representation to critical narrative as the researcher moves from the ontological rigidity of the text to the analytical fluidity of the account of the film they present. Figure 2.3 illustrates this process.

![The transformational process of computationally analysing a short horror film [@redfern2015ttcp]. The film is processed to extract the selected data required for analysis, with film and data being equivalent. In turn, this data is processed to produce a set of projections (visualisations, numerical summaries, etc.) that represent the structure of the film. These representations are the basis for a critical narrative that explains a range of features of the film. ☝️](Images/cfa-film-plot-transformations.png)

Figure 2.3: The transformational process of computationally analysing a short horror film (Redfern, 2015b). The film is processed to extract the selected data required for analysis, with film and data being equivalent. In turn, this data is processed to produce a set of projections (visualisations, numerical summaries, etc.) that represent the structure of the film. These representations are the basis for a critical narrative that explains a range of features of the film. ☝️

2.4.3 Computational

Digital Humanities is a broad term that includes all the works of humanists who use digital methods and materials (Ramsay, 2012b). Some digital humanists will employ existing available technologies such as Voyant Tools, VIAN (Flueckiger & Halter, 2020), or ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012) to process texts; others will create their own tools, developing new software or writing code for analysis. The computational humanities are thus a part of but are not co-extensive with the digital humanities; you do not have to be able to code to be a digital humanist. As Birnbaum & Langmead (2017: 64) point out, ‘Digital Humanities is a way of doing humanities, not a way of doing computing.’

While not every digital humanist needs to be able to code, there are advantages in acquiring a knowledge of how to develop tools and process data for the digital humanities. Understanding how software for the digital humanities is developed and how it operates allows researchers to use existing tools more effectively and to find ways to ‘hack’ those tools to use them in new ways (Birnbaum & Langmead, 2017). Going further, learning how to code means that digital humanists are not restricted to the procedural logic designed into tools by their creators and can create their own tools according to the workflows required by their own research projects. Learning to code can therefore be a source of independence for researchers. At the same time, digital humanities projects often bring together groups of researchers with different types of knowledge, and an understanding of the tools and logic that underpins a research project is required for collaboration. Learning to code creates opportunities for discovery, enabling researchers to play with texts and test and refine ways on producing knowledge about them. Such ‘exploratory programming’ (Montfort, 2021) can lead to new ways of thinking about problems or to conceive new methods of analysis. Developing tools is itself a form of humanities research, with a different set out outputs (data sets, data papers, software, databases, etc.) through which knowledge is shared beyond the traditional six-to-eight-thousand-word article (though the digital humanities remain devoted to communicating knowledge in this form). Finally, there is much satisfaction to be gained from writing the code that reveals some new aspect of a text or lets us see a topic in a new way, or in developing a tool that will enable others to do the same. As an act of creative problem solving, coding is a source of pleasure in research.

2.5 Summary

Computational film analysis is a digital humanities approach to understanding style in the cinema. It is only a one such approach among many (Burghardt et al., 2020); but as the name indicates, it is one that is based on a proficiency in creating and applying tools through coding. Referring to the model of a CFA project described in Figure 2.1, it is necessary for scholars to understand both the quantitative methods employed and how those methods are operationalized as software. These are topics that Film Studies scholars have traditionally shied away from but the bar to entry is low, requiring only (1) a recognition that computational tools can be useful in helping us to understand form and style in the cinema and (2) the time to acquire the requisite knowledge. The subsequent chapters of this book present some methods using the R statistical programming language within the CFA framework described above for the analysis of film form and style, demonstrating their application and making explicit the concepts and logic that underpin them. What the reader/user/explorer chooses to do with these methods will create new knowledge and tools for creating knowledge about the cinema.